指针是 C++ 历史上的“吓人精”之一,也是许多有抱负的 C++ 学习者感到困惑的地方。然而,正如你很快就会看到的,指针并不可怕。

事实上,指针的行为很像左值引用。但在我们进一步解释之前,让我们做一些准备工作。

相关内容

如果你对左值引用生疏或不熟悉,现在是回顾它们的好时机。我们在第 12.3 -- 左值引用、12.4 -- 对常量的左值引用 和 12.5 -- 按左值引用传递 课程中涵盖了左值引用。

考虑一个普通变量,例如这个

char x {}; // chars use 1 byte of memory简化一下,当为这个定义生成的代码执行时,RAM 中的一块内存将被分配给这个对象。举例来说,假设变量 `x` 被分配了内存地址 `140`。每当我们使用变量 `x` 在表达式或语句中时,程序将转到内存地址 `140` 来访问存储在那里的值。

变量的好处在于我们不需要担心分配了哪些特定的内存地址,或者存储对象值需要多少字节。我们只需通过其给定的标识符来引用变量,编译器会将这个名称转换为适当分配的内存地址。编译器负责处理所有寻址。

引用也是如此

int main()

{

char x {}; // assume this is assigned memory address 140

char& ref { x }; // ref is an lvalue reference to x (when used with a type, & means lvalue reference)

return 0;

}因为 `ref` 作为 `x` 的别名,每当我们使用 `ref` 时,程序将转到内存地址 `140` 来访问该值。同样,编译器会处理寻址,这样我们就不必考虑它。

取址运算符 (&)

尽管变量使用的内存地址默认不会向我们公开,但我们可以访问这些信息。**取址运算符** (&) 返回其操作数的内存地址。这非常直观

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

int x{ 5 };

std::cout << x << '\n'; // print the value of variable x

std::cout << &x << '\n'; // print the memory address of variable x

return 0;

}在作者的机器上,上述程序打印了

5 0027FEA0

在上面的例子中,我们使用取址运算符(&)检索分配给变量 `x` 的地址,并将该地址打印到控制台。内存地址通常以十六进制值打印(我们在第 5.3 -- 数字系统(十进制、二进制、十六进制和八进制) 课程中介绍了十六进制),通常不带 0x 前缀。

对于使用多个字节内存的对象,取址运算符将返回对象使用的第一个字节的内存地址。

提示

& 符号容易引起混淆,因为它在不同的上下文中有不同的含义

- 当跟在类型名称后面时,& 表示一个左值引用:`int& ref`。

- 当在表达式中作为一元运算符使用时,& 是取址运算符:`std::cout << &x`。

- 当在表达式中作为二元运算符使用时,& 是位与运算符:`std::cout << x & y`。

解引用运算符 (*)

单独获取变量的地址并没有多大用处。

我们可以对地址做的最有用的事情是访问存储在该地址的值。**解引用运算符** (*)(有时也称为**间接运算符**)将给定内存地址处的值作为左值返回

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

int x{ 5 };

std::cout << x << '\n'; // print the value of variable x

std::cout << &x << '\n'; // print the memory address of variable x

std::cout << *(&x) << '\n'; // print the value at the memory address of variable x (parentheses not required, but make it easier to read)

return 0;

}在作者的机器上,上述程序打印了

5 0027FEA0 5

这个程序非常简单。首先,我们声明一个变量 `x` 并打印它的值。然后我们打印变量 `x` 的地址。最后,我们使用解引用运算符获取变量 `x` 的内存地址处的值(这只是 `x` 的值),然后将其打印到控制台。

关键见解

给定一个内存地址,我们可以使用解引用运算符 (*) 获取该地址处的值(作为左值)。

取址运算符(&)和解引用运算符(*)的作用相反:取址运算符获取对象的地址,解引用运算符获取地址处的对象。

提示

虽然解引用运算符看起来与乘法运算符相同,但你可以通过它们是单元运算符而乘法运算符是二元运算符来区分它们。

获取变量的内存地址然后立即解引用该地址以获取值也没有那么有用(毕竟,我们可以直接使用变量来访问该值)。

但是现在我们已经将取址运算符 (&) 和解引用运算符 (*) 添加到我们的工具包中,我们准备好谈论指针了。

指针

**指针**是一个对象,其值**存储内存地址**(通常是另一个变量的地址)。这使我们能够存储其他对象的地址,以便稍后使用。

题外话…

在现代 C++ 中,我们这里谈论的指针有时被称为“原始指针”或“笨指针”,以帮助将它们与最近引入语言的“智能指针”区分开来。我们在第 22 章中介绍智能指针。

指定指针的类型(例如 `int*`)称为**指针类型**。就像引用类型使用 & 字符声明一样,指针类型使用星号 (*) 声明

int; // a normal int

int&; // an lvalue reference to an int value

int*; // a pointer to an int value (holds the address of an integer value)要创建一个指针变量,我们只需定义一个指针类型的变量

int main()

{

int x { 5 }; // normal variable

int& ref { x }; // a reference to an integer (bound to x)

int* ptr; // a pointer to an integer

return 0;

}请注意,此星号是指针声明语法的一部分,而不是解引用运算符的使用。

最佳实践

声明指针类型时,将星号放在类型名称旁边。

警告

尽管通常不应在一行中声明多个变量,但如果这样做,星号必须包含在每个变量中。

int* ptr1, ptr2; // incorrect: ptr1 is a pointer to an int, but ptr2 is just a plain int!

int* ptr3, * ptr4; // correct: ptr3 and ptr4 are both pointers to an int虽然这有时被用作不将星号放在类型名称旁边(而是将其放在变量名称旁边)的论据,但它更好地说明了避免在同一语句中定义多个变量的理由。

指针初始化

与普通变量一样,指针默认情况下**不**进行初始化。未初始化的指针有时称为**野指针**。野指针包含一个垃圾地址,解引用野指针将导致未定义行为。因此,您应该始终将指针初始化为已知值。

最佳实践

始终初始化你的指针。

int main()

{

int x{ 5 };

int* ptr; // an uninitialized pointer (holds a garbage address)

int* ptr2{}; // a null pointer (we'll discuss these in the next lesson)

int* ptr3{ &x }; // a pointer initialized with the address of variable x

return 0;

}由于指针保存地址,当我们初始化或赋值给指针时,该值必须是一个地址。通常,指针用于保存另一个变量的地址(我们可以使用取址运算符 (&) 获取)。

一旦我们有一个指向另一个对象的指针,我们就可以使用解引用运算符 (*) 来访问该地址的值。例如

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

int x{ 5 };

std::cout << x << '\n'; // print the value of variable x

int* ptr{ &x }; // ptr holds the address of x

std::cout << *ptr << '\n'; // use dereference operator to print the value at the address that ptr is holding (which is x's address)

return 0;

}这会打印

5 5

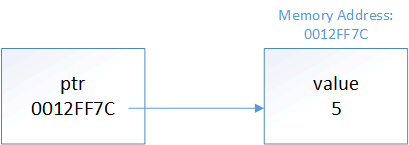

从概念上讲,你可以这样理解上面的代码片段

这就是指针得名的原因——`ptr` 存放着 `x` 的地址,所以我们说 `ptr` “指向” `x`。

作者注

关于指针命名法的一个注释:“X 指针”(其中 X 是某种类型)是“指向 X 的指针”的常用缩写。所以当我们说“一个整数指针”时,我们实际指的是“一个指向整数的指针”。当我们讨论 const 指针时,这种理解将非常有价值。

就像引用的类型必须与被引用的对象的类型匹配一样,指针的类型也必须与被指向的对象的类型匹配。

int main()

{

int i{ 5 };

double d{ 7.0 };

int* iPtr{ &i }; // ok: a pointer to an int can point to an int object

int* iPtr2 { &d }; // not okay: a pointer to an int can't point to a double object

double* dPtr{ &d }; // ok: a pointer to a double can point to a double object

double* dPtr2{ &i }; // not okay: a pointer to a double can't point to an int object

return 0;

}除了我们下一课将讨论的一个例外,用字面值初始化指针是不允许的

int* ptr{ 5 }; // not okay

int* ptr{ 0x0012FF7C }; // not okay, 0x0012FF7C is treated as an integer literal指针与赋值

我们可以通过两种不同的方式对指针进行赋值

- 更改指针指向的位置(通过为指针分配新地址)

- 更改被指向的值(通过给解引用指针赋新值)

首先,我们来看一个指针更改为指向不同对象的情况

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

int x{ 5 };

int* ptr{ &x }; // ptr initialized to point at x

std::cout << *ptr << '\n'; // print the value at the address being pointed to (x's address)

int y{ 6 };

ptr = &y; // // change ptr to point at y

std::cout << *ptr << '\n'; // print the value at the address being pointed to (y's address)

return 0;

}上面打印

5 6

在上面的例子中,我们定义了指针 `ptr`,用 `x` 的地址初始化它,然后解引用指针以打印被指向的值(`5`)。然后我们使用赋值运算符将 `ptr` 持有的地址更改为 `y` 的地址。然后我们再次解引用指针以打印被指向的值(现在是 `6`)。

现在让我们看看如何使用指针来更改所指向的值

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

int x{ 5 };

int* ptr{ &x }; // initialize ptr with address of variable x

std::cout << x << '\n'; // print x's value

std::cout << *ptr << '\n'; // print the value at the address that ptr is holding (x's address)

*ptr = 6; // The object at the address held by ptr (x) assigned value 6 (note that ptr is dereferenced here)

std::cout << x << '\n';

std::cout << *ptr << '\n'; // print the value at the address that ptr is holding (x's address)

return 0;

}这个程序打印

5 5 6 6

在这个例子中,我们定义了指针 `ptr`,用 `x` 的地址初始化它,然后打印 `x` 和 `*ptr` 的值(`5`)。因为 `*ptr` 返回一个左值,所以我们可以在赋值语句的左侧使用它,从而将 `ptr` 指向的值更改为 `6`。然后我们再次打印 `x` 和 `*ptr` 的值,以显示值已按预期更新。

关键见解

当我们不带解引用地使用指针(`ptr`)时,我们正在访问指针所持有的地址。修改它(`ptr = &y`)会改变指针指向的位置。

当我们解引用指针(`*ptr`)时,我们正在访问被指向的对象。修改它(`*ptr = 6;`)会改变被指向对象的值。

指针的行为很像左值引用

指针和左值引用的行为相似。考虑以下程序

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

int x{ 5 };

int& ref { x }; // get a reference to x

int* ptr { &x }; // get a pointer to x

std::cout << x;

std::cout << ref; // use the reference to print x's value (5)

std::cout << *ptr << '\n'; // use the pointer to print x's value (5)

ref = 6; // use the reference to change the value of x

std::cout << x;

std::cout << ref; // use the reference to print x's value (6)

std::cout << *ptr << '\n'; // use the pointer to print x's value (6)

*ptr = 7; // use the pointer to change the value of x

std::cout << x;

std::cout << ref; // use the reference to print x's value (7)

std::cout << *ptr << '\n'; // use the pointer to print x's value (7)

return 0;

}这个程序打印

555 666 777

在上面的程序中,我们创建了一个值为 `5` 的普通变量 `x`,然后创建了一个左值引用和一个指向 `x` 的指针。接下来,我们使用左值引用将值从 `5` 更改为 `6`,并展示可以通过这三种方法访问更新后的值。最后,我们使用解引用指针将值从 `6` 更改为 `7`,并再次展示可以通过这三种方法访问更新后的值。

因此,指针和引用都提供了一种间接访问另一个对象的方法。主要区别在于,对于指针,我们需要显式获取要指向的地址,并且必须显式解引用指针才能获取值。而对于引用,取址和解引用是隐式发生的。

指针和引用之间还有一些其他值得一提的区别

- 引用必须初始化,指针不要求初始化(但应该初始化)。

- 引用不是对象,指针是对象。

- 引用不能被重新绑定(更改为引用其他东西),指针可以改变它们指向的对象。

- 引用必须始终绑定到一个对象,指针可以指向空(我们将在下一课中看到一个例子)。

- 引用是“安全的”(悬空引用除外),指针本质上是危险的(我们将在下一课中讨论这个问题)。

取址运算符返回一个指针

值得注意的是,取址运算符 (&) 不会将其操作数的地址作为字面量返回(因为 C++ 不支持地址字面量)。相反,它返回一个指向操作数的指针(其值为操作数的地址)。换句话说,给定变量 `int x`,`&x` 返回一个持有 `x` 地址的 `int*`。

我们可以在下面的例子中看到这一点

#include <iostream>

#include <typeinfo>

int main()

{

int x{ 4 };

std::cout << typeid(x).name() << '\n'; // print the type of x

std::cout << typeid(&x).name() << '\n'; // print the type of &x

return 0;

}在 Visual Studio 上,这打印了

int int *

使用 gcc 时,它打印的是 `i` (int) 和 `pi` (pointer to int)。因为 `typeid().name()` 的结果是依赖于编译器的,所以你的编译器可能会打印出不同的内容,但它们具有相同的含义。

指针的大小

指针的大小取决于可执行文件编译的架构——32 位可执行文件使用 32 位内存地址——因此,32 位机器上的指针是 32 位(4 字节)。对于 64 位可执行文件,指针将是 64 位(8 字节)。请注意,无论被指向对象的大小如何,这都成立

#include <iostream>

int main() // assume a 32-bit application

{

char* chPtr{}; // chars are 1 byte

int* iPtr{}; // ints are usually 4 bytes

long double* ldPtr{}; // long doubles are usually 8 or 12 bytes

std::cout << sizeof(chPtr) << '\n'; // prints 4

std::cout << sizeof(iPtr) << '\n'; // prints 4

std::cout << sizeof(ldPtr) << '\n'; // prints 4

return 0;

}指针的大小始终相同。这是因为指针只是一个内存地址,访问内存地址所需的位数是恒定的。

悬空指针

就像悬空引用一样,**悬空指针**是指指向不再有效的对象地址(例如,因为它已被销毁)的指针。

解引用悬空指针(例如,为了打印所指向的值)将导致未定义行为,因为您正在尝试访问不再有效的对象。

或许令人惊讶的是,标准规定“对无效指针值的任何其他使用都具有实现定义的行为”。这意味着您可以为无效指针分配一个新值,例如 nullptr(因为这不会使用无效指针的值)。然而,任何其他使用无效指针值的操作(例如复制或递增无效指针)都将产生实现定义的行为。

关键见解

解引用无效指针将导致未定义行为。对无效指针值的任何其他使用都是实现定义的。

这是一个创建悬空指针的例子

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

int x{ 5 };

int* ptr{ &x };

std::cout << *ptr << '\n'; // valid

{

int y{ 6 };

ptr = &y;

std::cout << *ptr << '\n'; // valid

} // y goes out of scope, and ptr is now dangling

std::cout << *ptr << '\n'; // undefined behavior from dereferencing a dangling pointer

return 0;

}上面的程序可能会打印

5 6 6

但它可能不会,因为 `ptr` 所指向的对象在内部块结束时超出了范围并被销毁,导致 `ptr` 悬空。

总结

指针是存储内存地址的变量。它们可以使用解引用运算符 (*) 解引用,以检索其所持地址处的值。解引用野指针或悬空指针(或空指针)将导致未定义行为,并可能使您的应用程序崩溃。

指针比引用更灵活,也更危险。我们将在接下来的课程中继续探讨这一点。

小测验时间

问题 #1

这个程序会打印什么值?假设 `short` 是 2 字节,并且是 32 位机器。

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

short value{ 7 }; // &value = 0012FF60

short otherValue{ 3 }; // &otherValue = 0012FF54

short* ptr{ &value };

std::cout << &value << '\n';

std::cout << value << '\n';

std::cout << ptr << '\n';

std::cout << *ptr << '\n';

std::cout << '\n';

*ptr = 9;

std::cout << &value << '\n';

std::cout << value << '\n';

std::cout << ptr << '\n';

std::cout << *ptr << '\n';

std::cout << '\n';

ptr = &otherValue;

std::cout << &otherValue << '\n';

std::cout << otherValue << '\n';

std::cout << ptr << '\n';

std::cout << *ptr << '\n';

std::cout << '\n';

std::cout << sizeof(ptr) << '\n';

std::cout << sizeof(*ptr) << '\n';

return 0;

}问题 #2

这段代码有什么问题?

int v1{ 45 };

int* ptr{ &v1 }; // initialize ptr with address of v1

int v2 { 78 };

*ptr = &v2; // assign ptr to address of v2